PARCHMENT IN THE HISTORY OF WRITING SUPPLIES

Autor:

Mari Siiner

Year:

Anno 2017/2018

Category:

Digitisation

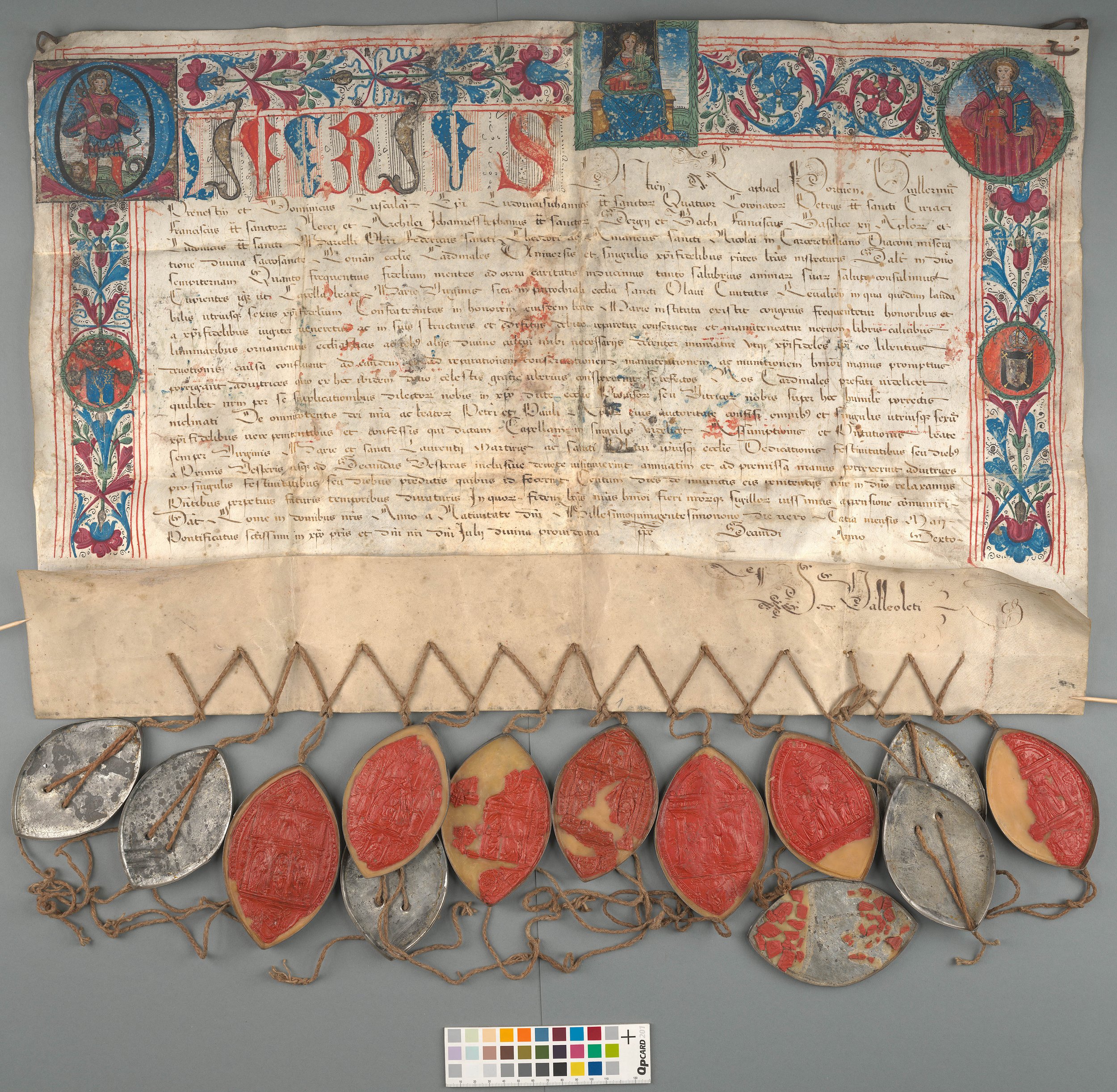

The phenomenon of the nearly a couple of tho1usand years old parchment documents that have preserved up to our time totally justifies our conception of parchment as a mysterious and wonderful writing material [fig 1].

The terms – ‘parchment’ and ‘vellum’2 that were initially used only for animal-based materials have today become synonymous to many other high-quality, heavy-duty materials not animal-based at all. So, for example the word parchment paper is used for different kinds of paper, such as paper vellum made of plasticised cotton fibre, heatproof paper, oil-bitumen impregnated cardboard or the vegetarian partly transparent parchment paper. So today we have become somewhat confused in the interpretation of these various terms. The confusion is felt even more when the basic knowledge about parchment as an animal-based writing material is missing. The present paper is a survey of parchment as specially treated animal leather used for writing. The first word for treated skin in Latin – memranae – was later replaced either by repyapsivi, charta (a thin sheet) or pergamena. The last of them became the root for parchment in English, parchemin in French and also pärgament in Estonian.

The invention and development of parchment as a special writing supply is closely connected with the evolving skills how to treat and work with mammals’ hide and skin but it also depended on the invention of writing. The writing supplies depended on the regional natural possibilities and the opportunities of learning to write and develop the skill.

Using leather for writing evidently dates back to the pre-dynasty period of Egyptian pharaohs, when it was used simultaneously with stone, wood and bone for putting down hieroglyphs, i.e. about 5000 years ago (3200-3000 BC).3 The oldest leather rolls date from the Middle-State period (2055-1650 BC).4 These finds are really rare, as at that time animal skin and hide were not much used in Egypt any longer and they had mostly been replaced by papyrus.

Differently from Egypt many other regions in the Middle-East (like Syria and Persia), in the Roman and Greek areas and Palestine still used leather together with papyrus up to the beginning of mass production of parchment in the 2nd century BC. Assyrians and Babylonians used animal skin simultaneously with clay tablets for their hieroglyphics. The first descriptions about tanning animal hide and skin with animal (brains, marrow, fat) and vegetative (bark, roots, leaves) tannins come from Ancient Orient higher civilisations, Babylonian and Egyptian among them, and date back to about 2000-1600 BC.

A great change in working the animal skin for writing supplies took place in the Hellenic period (323-30 BC) thanks, above all, to the rapid development of culture and science. Libraries and centres of science appeared in the capital cities of Hellenistic kingdoms. Alexandria in Egypt, Pergamon in Asia Minor and Antiokia in Syria should be mentioned as essential centres of Hellenistic culture and science.

The economic prosperity of Hellenistic states in the 3rd century BC was pretty soon replaced by deepening political and economic crises, brought on by wars and quarrels of sovereigns around the Mediterranean Sea. The republic of Rome intervened in these wars more and more often (like, for instance in the case of the Macedonian-Roman wars). Rivalry between the King of Egypt, Ptolemy V Epiphanes (reigned in 204-181 BC) and the King of Pergamon, Eumenes (reigned in 197-158 BC) evolved to such an extent that when the library in Pergamon was enlarged and more papyrus needed, King Ptolemy cancelled the export of it to Egypt. Thus they still had to use leather and so they began to develop and improve its quality. The result was a much better parchment to write on.4 The leather treated like that got its name after the biggest centre where it was produced – Pergamon (today Bergama in Turkey). The word for word translation of parchment in Latin and Greek is ‘comes from Pergamon’.

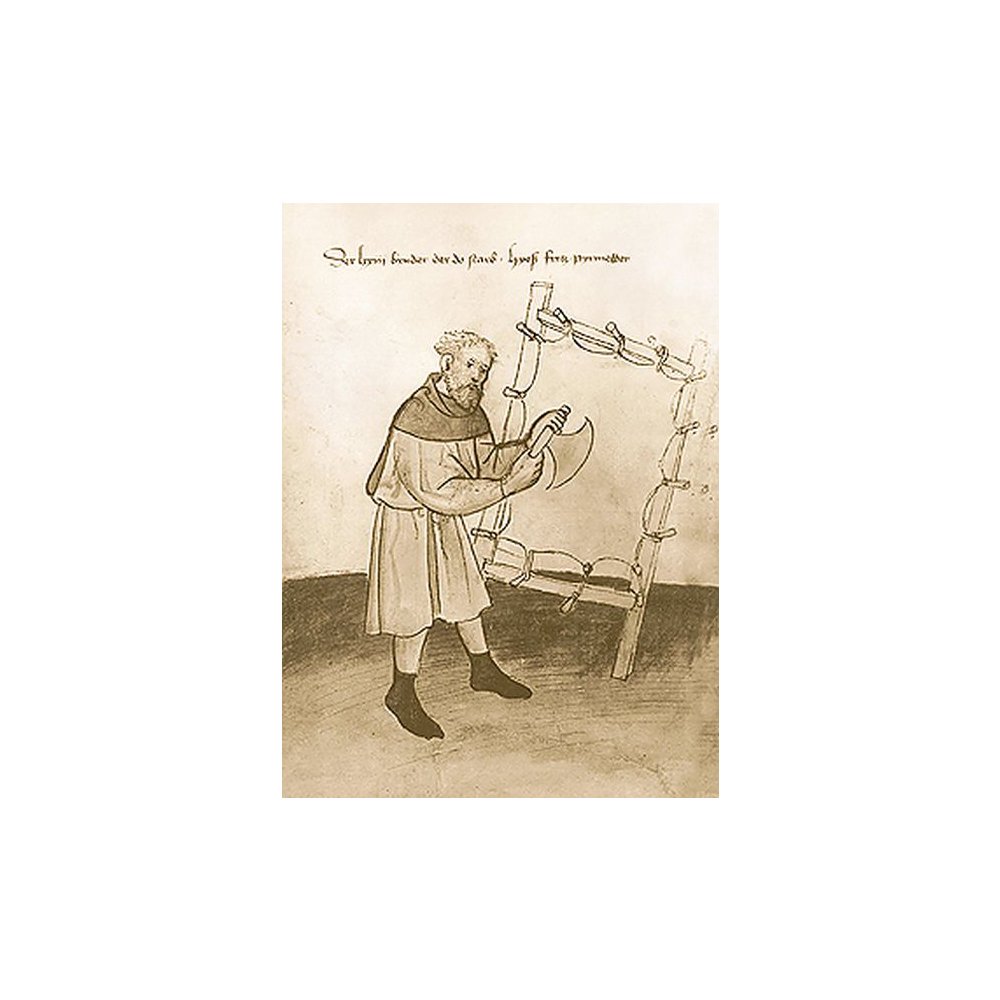

While up to then animal and vegetal tannins had been used for treating the skins and hides, the novel tanning methods gave the traditional ones up. Careful selection of raw hide before treating began granted the final high quality of leather together with the technology that was subjected to precise rules – the procedure. Notable changes in the new ways of tanning were the repeated use of slaked lime before and after the hairs had been removed, the repeated mechanical treating, drying and stretching of the surface on a frame. After liming the leather was carefully washed to get rid of the treating remnants. Then both sides of the leather were scraped and stretched to make it uniformly thinner and smoother. In addition to scraping mechanical splitting was introduced – it meant the total removal of either the thin upper or lower layer. Owing to the character of different layers, it is possible to separate them and simple procedures allow splitting all over the surface quite easily. Wet leather was stretched on the drying frame. When it was drying it was continuously thinned and stretched [fig. 2] [fig.3], [fig.3a]. The longer and more uniformly the stretching took the better was the result achieved. Before the drying process was completed the surface of the leather was rubbed with a powder of mixed chalk and pumice, in order to get the surface smoother and better ink-connective. This was a technology that granted good results – the uniformly smooth-surfaced leather was easy to roll up and the bilateral final treatment allowed both sides to be used for writing (recto, verso).

Experiments to make writing supplies of animal hides have been made elsewhere as well. So, for example, fragments of camel hides treated like parchment have been found in the area of Hebron (today Jordan).5

The oldest parchments with text could be the rolls, dating from 165-170 AD, found at the archaeological excavations in Dura-Europos (Syria today) castle in 1923.6

The real fame of the high-quality parchment mass production, though, definitely belongs to Pergamon.

As the raw material for making parchment was available everywhere, parchment was widely preferred to papyrus as a writing supply and by the 3rd century it had become common also in Europe.

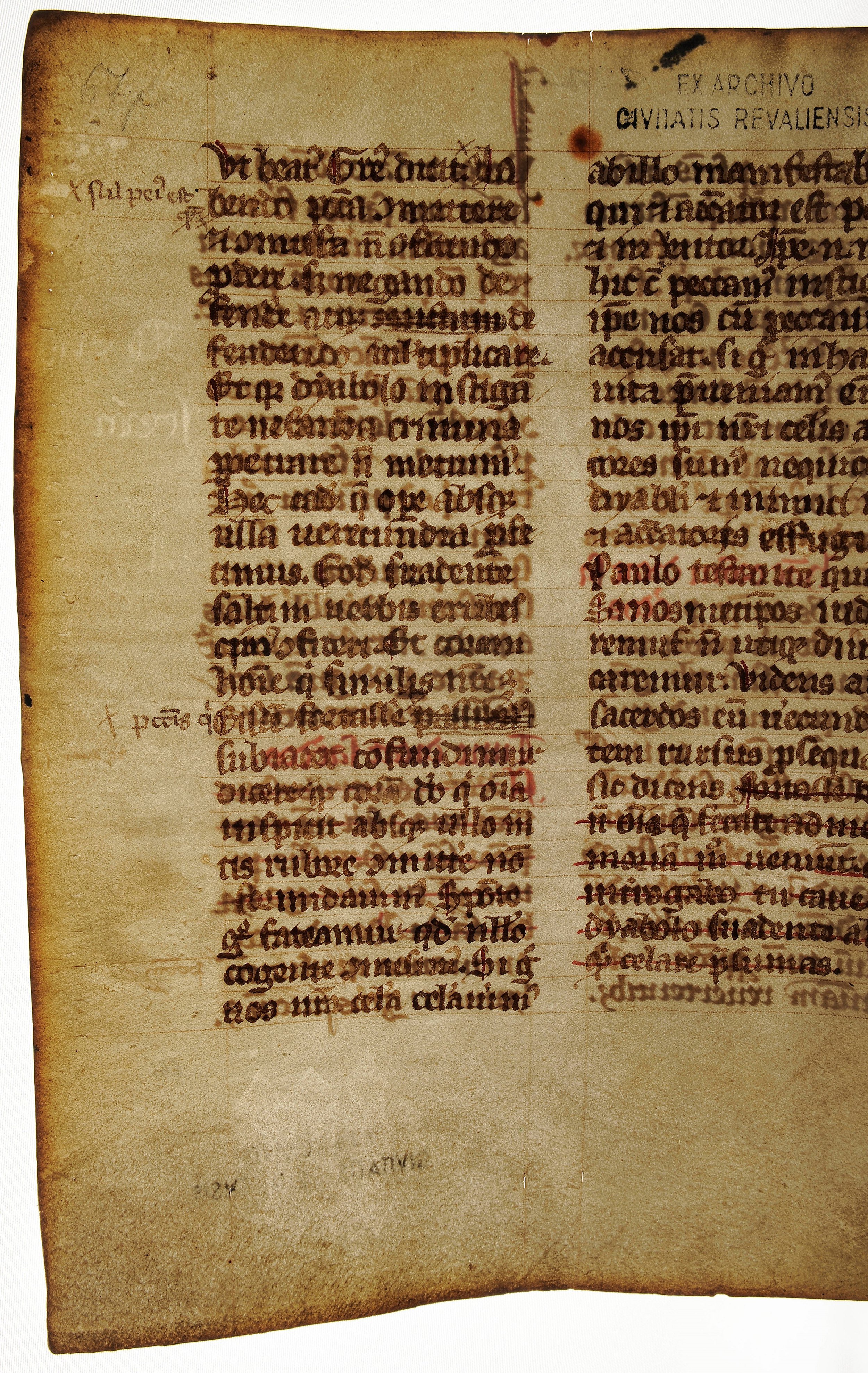

Another asset of parchment compared to papyrus was the possibility to scratch the mistake off the surface and make a correction in the text, writing it again7 [fig. 4], [fig.5].

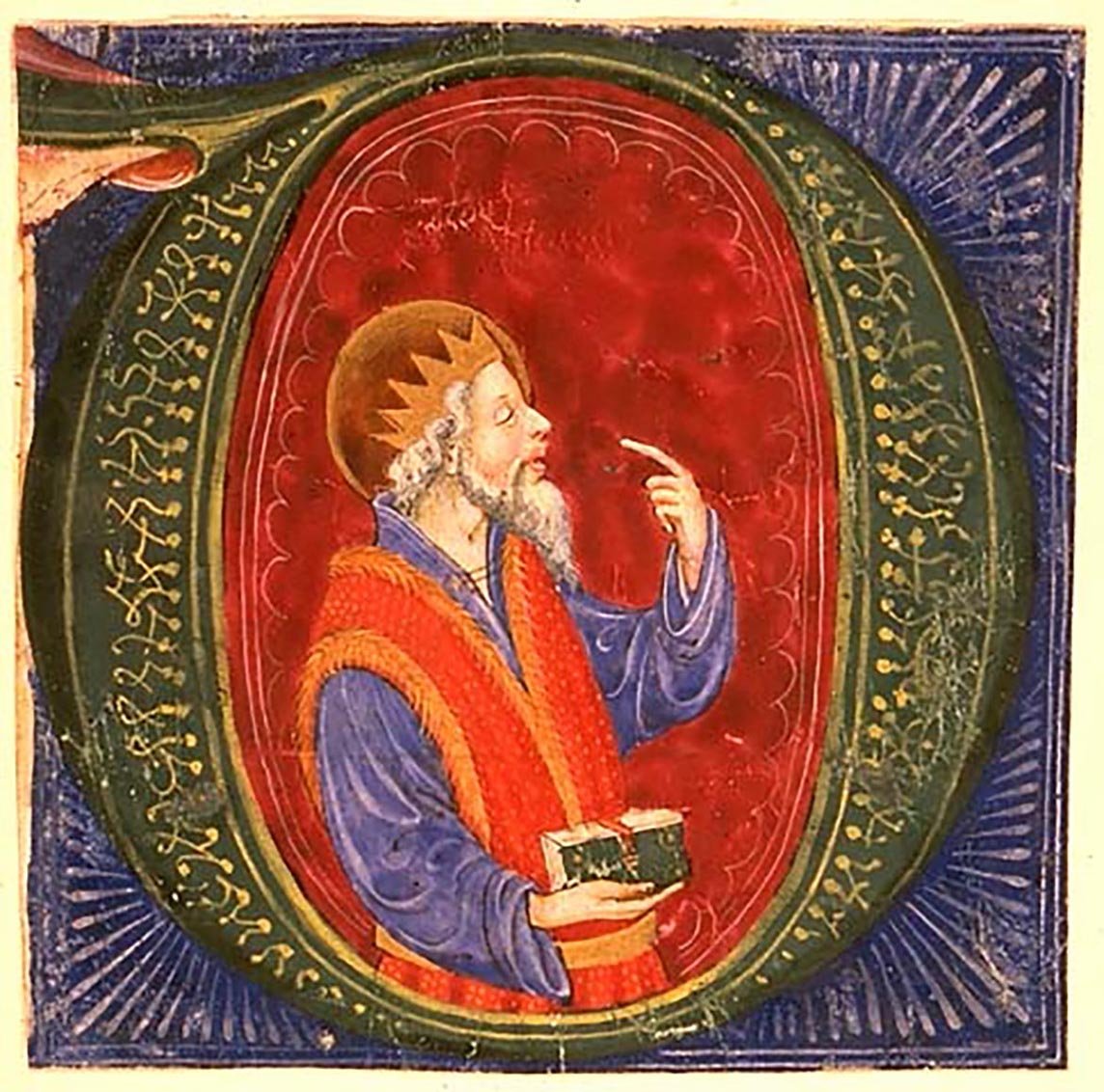

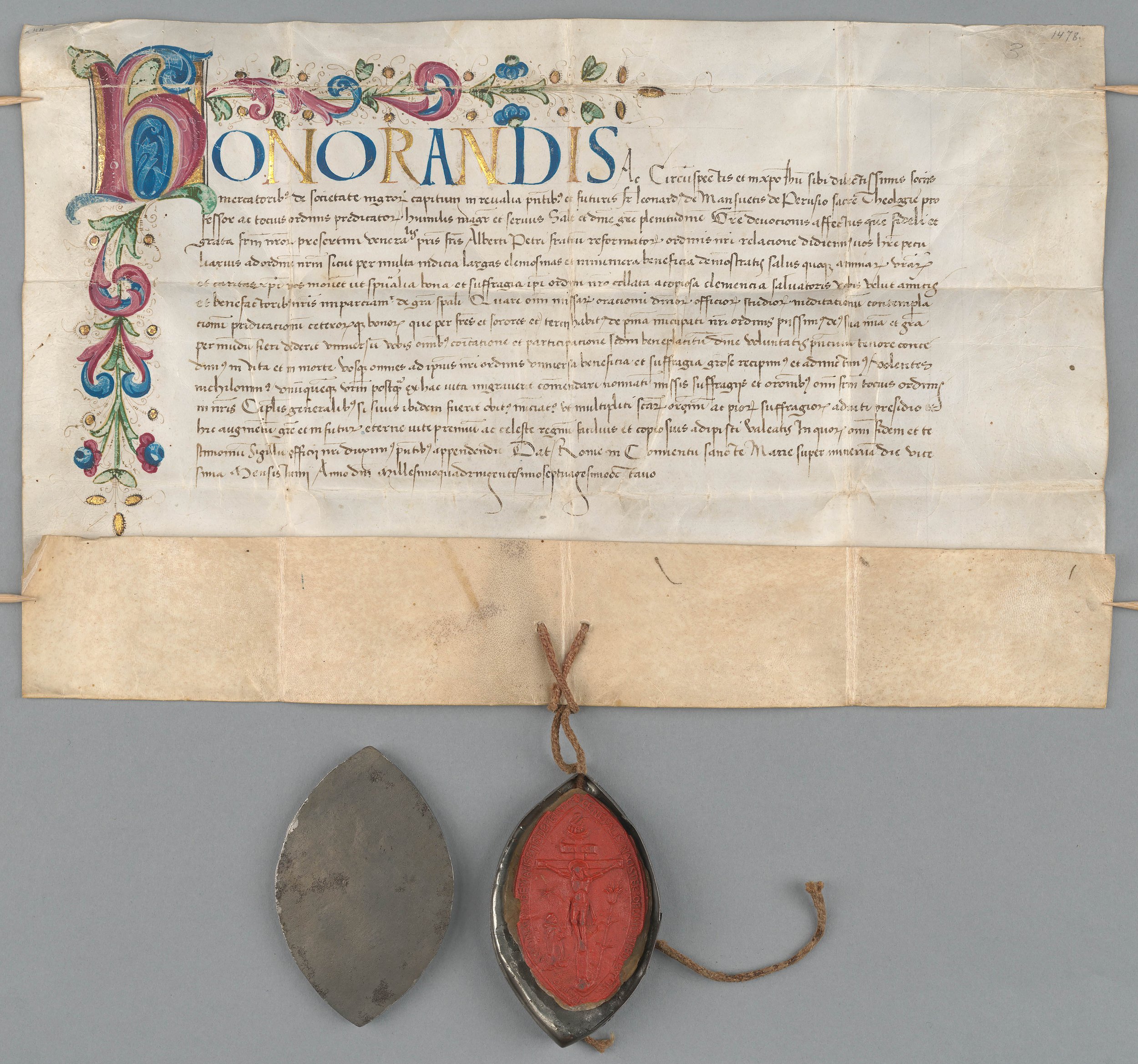

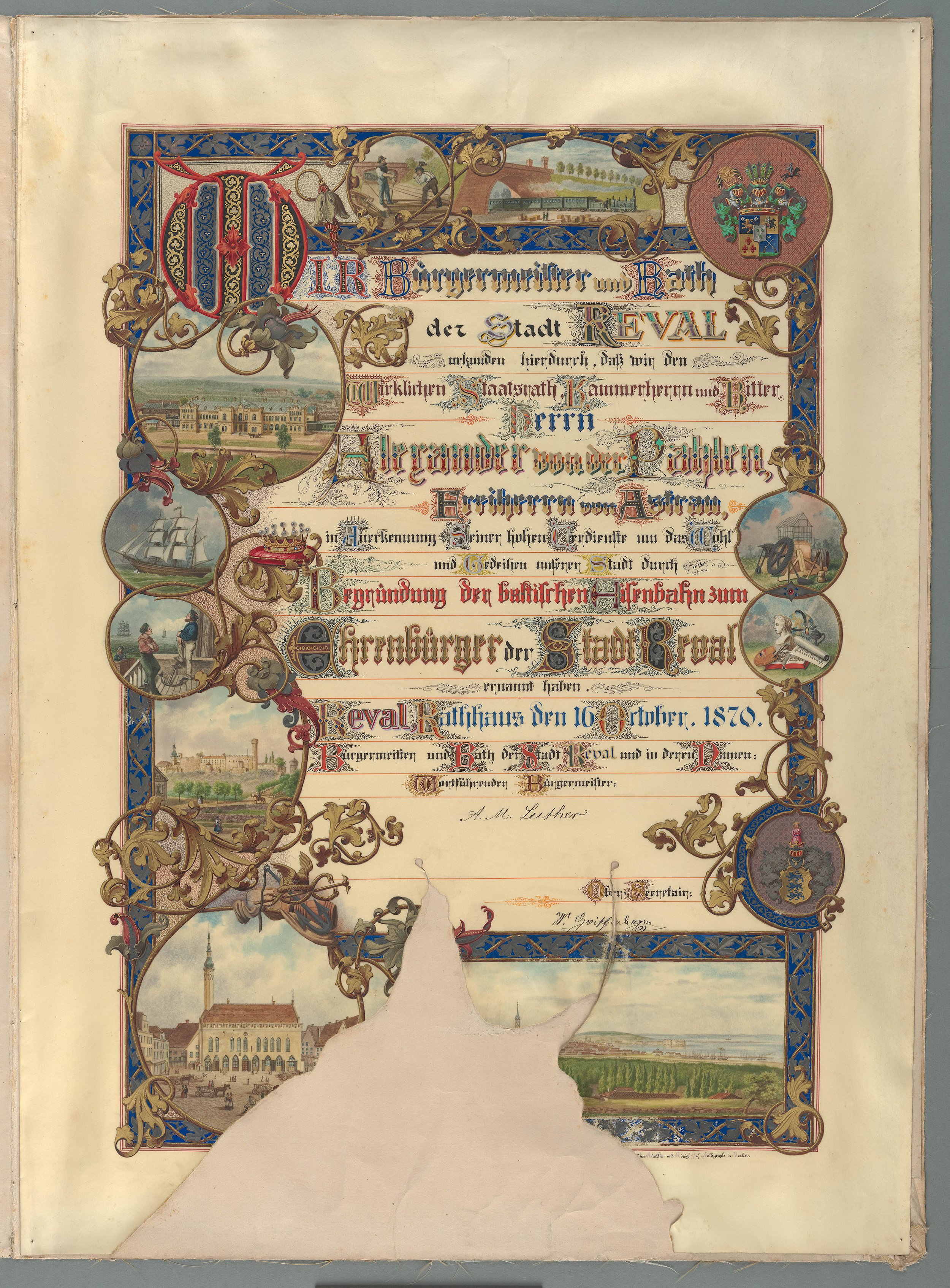

The reputation of this rare and resistant material survived even in the period (after the 12th century) when it was used simultaneously with rag-paper. So, for example, the thin elastic parchment became a fashionable trend for manuscript volumes richly decorated with gold and silver [fig.6], [fig.7], [fig.8], [fig.9], [fig.10] [fig.11] The trend survived throughout the Middle Ages and even later when the printing press was introduced and paper taken into use. Important manuscripts, richly illuminated were still on parchment even in the 16th century. And this brought along reforms in making parchment as a writing supply. So, for instance, Edwards of Halifax patented a technology of making transparent parchment in 1780. The transparency was achieved not only by stretching and splitting but also by treating the lower layer with the solution of potassium carbonate (K2CO3).8

The continuously growing demand for parchment had brought along a sort of decreasing quality of it already since the 6th century. The essential fall in the quality occurred in the 15th-16th centuries when it was thought that mono-lateral scraping and some finishing touches would have to do.

By the 16th9 century paper had become the most-used material for documents but for very important documents parchment still had preserved its reputation of longevity and so the skills of making it survived. Modern parchment is still made and used today as well.

A good example of still using it, although the expenditure-changing policy of the government has caused its slowly fading away, is the parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain. They have been writing their legal acts on parchment since 1272. For almost six hundred years up to 1850 these acts were recorded in manuscript on vellum rolls. The biggest parchment roll, 348m i.e. nearly a quarter of a mile long was written in 1821. Beginning from 1850 the parliament had their documents printed on parchment as codices or folders in two copies. This tradition was kept alive until 2016.10 The medieval manuscripts9 of the parliamentary documents have been reprinted on paper in the 18th century and today they have been published in CD-ROM version The Parliament Rolls of Medieval England. The texts on the parchment rolls have been translated, transcribed and supplemented with historical surveys and they are available online.11 Considering the digital-era and economic saving purposes it is envisaged to replace parchment with long-lasting archive paper. The House of the Lords has estimated an economic saving of about 116 000 dollars or nearly 80 000 pounds per year if paper replaced parchment totally. In other words, about 130 calves would not be slaughtered every year, as these 500 pages of parchment would not be needed any longer. The centuries-long tradition of using parchment in the kingdom that survived the wars, revolutions, economic highs and lows may become extinct, victimised by the austerity of the 21st century.12

REFERENCES:

Vellum (Latin vitulinum, French velin). Vellum was originally a parchment made of the skin of an unborn calf, kid or lamb. Later on it became used for a high-quality parchment of calf’s skin that was treated on both sides. Vellum was thinner as the usual parchment as a rule, used for making the early (the 2nd – 12th century) manuscript (codices) volumes.

www.ancient.eu/ Egyptian Hieroglyphs

www.ancient.eu/ Egyptian Hieroglyphs, http:// dictionnaire.sensagent.leparisien.fr/Egyptian_Mathematical_Leather_Roll/en-en

Parchment is either not tanned or lightly-tanned raw leather, scraped clean and polished until smooth.

https://www.sca.org.au/scribe/articles/ parchment.htm. Dura-Europos; The Parchments and the Papyri George D. Kilpatrick The Book Before Printing: Ancient, Medieval and oriental By David Diringer. Dover Publications, Inc.New York, pp 190-191

Such sheets are called ‘palimpses’ (palimpsestos in Gr, palimpsest: ‘scratched or scraped again’ Engl.)

Limed [Ca (OH)2] leather contains badly-dissolving soap-like compounds. K2CO3 forms fatty acid sols (the so-called liquid soap) and helps to wash out the residual substances more easily (editorial note)

Bo Rudin, making Paper. Sweden, 1991

http://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/CBP-7451).

http://www.sdeditions.com/AnaAdditional/PROMEeg/Images/home.html.

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/11/world/ europe/critics-ruffled-as-parliament-turns-the-page-on-parchment.html).